Board Member Essay:Intergenerational Creative Communities for fsm.

by Emily Bowles

When I read Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own 25 or so years ago, I thought I’d discovered what was missing from my identity as a reader, writer, and woman: a lineage of authorship that valued and welcomed voices like mine. I was a Southern girl who’d spent more years than I care to acknowledge affecting a fake British accent to defy my roots, whose unfortunate bowl cut and stick-figure teenage body led to frequent misgenderings and bullying, and whose writing went from ubiquitous to absent once I (paradoxically) read Woolf and realized that I would never write with that luminescent beauty, equally capable of embracing the universal and making the particular uniquely accessible.

That’s why I sought out historical women’s writing. I wanted to build a family tree of sorts, one that showed not just me but others who felt marginalized, silenced, misremembered, or unheard that there were precedents and places for us, that others including Aphra Behn, Phylis Wheatley, Eliza Haywood, Charlotte Smith, Sarah Scott, Elizabeth Carter, Delarivier Manley, and so many more had written and been read, and that in rediscovering them, we could create nexuses of safety for speech, for self-expression.

Recovery work as an academic meant finding these women and recuperating them, often using a twinned tactic of formal critical appreciation (e.g., demonstrating that their works met and exceeded both aesthetic and commercial standards we have historically used only to qualify the works of men) and feminist literary theory. Over twenty years later, these women remind me that all voices have value, even when acts of violent suppression remove them—like Philomela’s tongue—from the literary canon.

What grad school did not, however, teach me was that archives are living, breathing things, and in searching for my own voice, I’ve discovered that every community has its own library of stories. Like many of us, though, I put the least value on the ones closest to me, subconsciously believing that “real” writers were different from my mother, my grandmother, and the people whose art felt almost too natural, too visceral to count, based on the constructs I’d internalized.

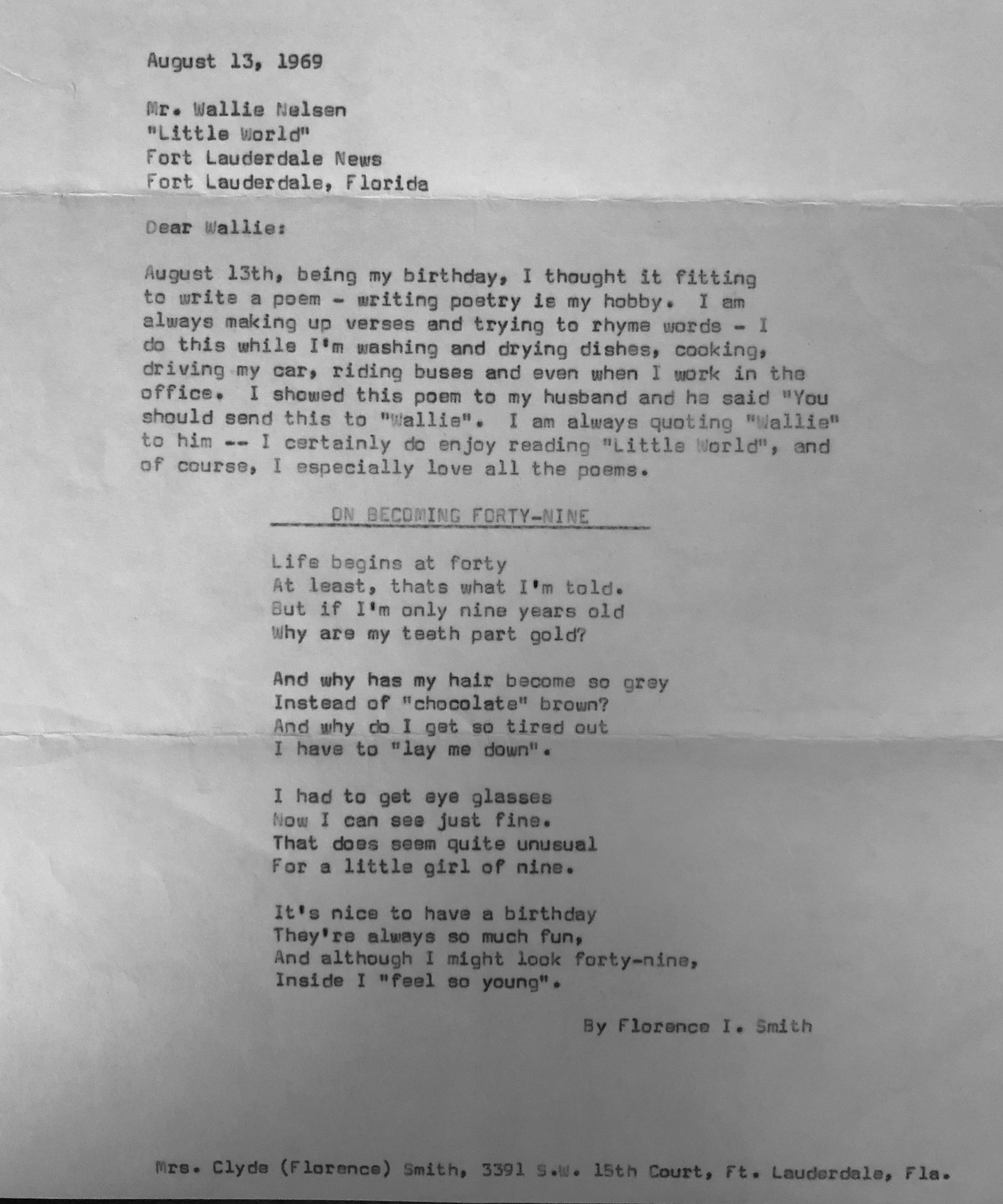

Now I see that my grandmother wrote poems that, had she read them at an open mic, I would have wished I’d written, and that my mother’s passion for libraries coupled with her later-in-life pursuit of a graduate degree that led her to teach Classical mythology played a critical role in inspiring me.

Like me, my grandmother struggled with anxiety, and the poetry she wrote is in many ways like mine, its surface concealing what she didn’t want to say yet needed to put on a page. She also found ways to make meaning when words failed or limited her: she made sock monkeys, stuffed dogs, and hippos, all of which I’ve stitched together now too, often during phases of writer’s block.

My mother is different. She’s never published poetry or viewed herself as a writer; however, she went back to grad school when I was in high school, and I have a copy of a Shakespeare edition with our mutual annotations. There’s a dialogue there that I didn’t see, a conversation we had across words and through them even when we weren’t talking about iambic pentameter.

I’ve even found community with my ex-husband’s wife’s mother, who is a local Poet Laureate and writes poetry that showcases the beauty of home, family, and place in ways that make me see this state—the state of Wisconsin, our states of being—in brilliant, beautiful new ways.

As creatives, it’s often easy to dismiss our origins, our closest antecedents in favor of what we’re led to believe has more aesthetic and intellectual value. When we do this, we’re losing site of our inherent worth—and continuing to marginalize voices, artwork, and artefacts that possess their own magic, bigger and more encompassing than anything we’re taught in school. As fsm. continues to grow, I hope others will discover in it space to share iterations of creativity that tell their stories rather than the stories we’re taught to appreciate or the ones we’re expected to share.