OP/ED: "Hunger Artist"

by Vic Neptune

Franz Kafka’s 1922 short story, “A Hunger Artist,” has as its premise a strange phenomenon going around in Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; something Kafka himself had witnessed. Men voluntarily on display inside cages, not eating, scrawny, ribs showing, circus-type performers, sometimes with accompanying signs claiming they hadn’t eaten in weeks or months. They acted as entertainment for passersby, their peculiar profession combining a hunger for food but also a hunger for attention.

In Kafka’s story, diminishing public interest in the eponymous protagonist leads to a diminishment in the man’s sense of importance to society. Hunger artists, by the time Kafka wrote the story, were on the wane, due perhaps to the recent Great War’s many tragedies, including displacement, famine, injuries, death, and rearrangement of nations’ borders. The Austro-Hungarian Empire itself, where Kafka lived throughout his life, ceased to exist with the close of the war. Power structures, nations, shrunk like a hunger artist, losing vitality in the face of other rising powers.

I’m struck by Kafka’s depiction in this story of a person whose suffering has become a spectacle to society. We have such phenomena today--Central Americans, including children, locked into cages in U.S. border states. We see this ongoing crime against humanity on television, on the internet, but nothing gets done about an ongoing policy carried out during the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations, each of them equally indifferent and equally guilty of child abuse and unjust handling of people who have come to the United States due to our country’s foreign policies that disrupt the societies of the nations from where the immigrants come.

Kafka’s “Artist,” unlike the caged people in Texas and other states, chooses to live in his cell, his true motives obscured by the act of doing such a bizarre thing. His job is to entertain passersby. He tours European cities, giving onlookers a view of suffering they don’t experience themselves. Like the Medieval Cathars, an offshoot of Gnostic Christianity deemed heretical and suppressed violently by the Catholic Church, the Hunger Artist’s goal seems to be to wither away, becoming a spirit inhabiting a body until the body releases that spirit in death. It is Kafka’s odd and dark sense of humor, present throughout much of his work, that he has this strange man voluntarily making himself into a show as he turns, slowly, to dust.

Our own entertainment and news media cultures exploit a similar kind of passive viewing. We see video footage of a disaster or propaganda about wars fought around the world. News headlines on our phones tease our minds with salacious, slanted, or bombastic statements. We make little or no effort to understand what’s really going on when we’re facing a spectacle. The spectacle distracts and even overwhelms us, banishing critical thinking as we allow profit-driven corporate news media to determine what’s going on and what it means: another way of saying that Chuck Todd of Meet the Press is not a brilliant man, but he is a good actor.

Politicians, too, making statements, performing while serving on their committees, are like Kafka’s character, in a cage; not hungry, physically, but the pursuit of power, too, generates a form of hunger.

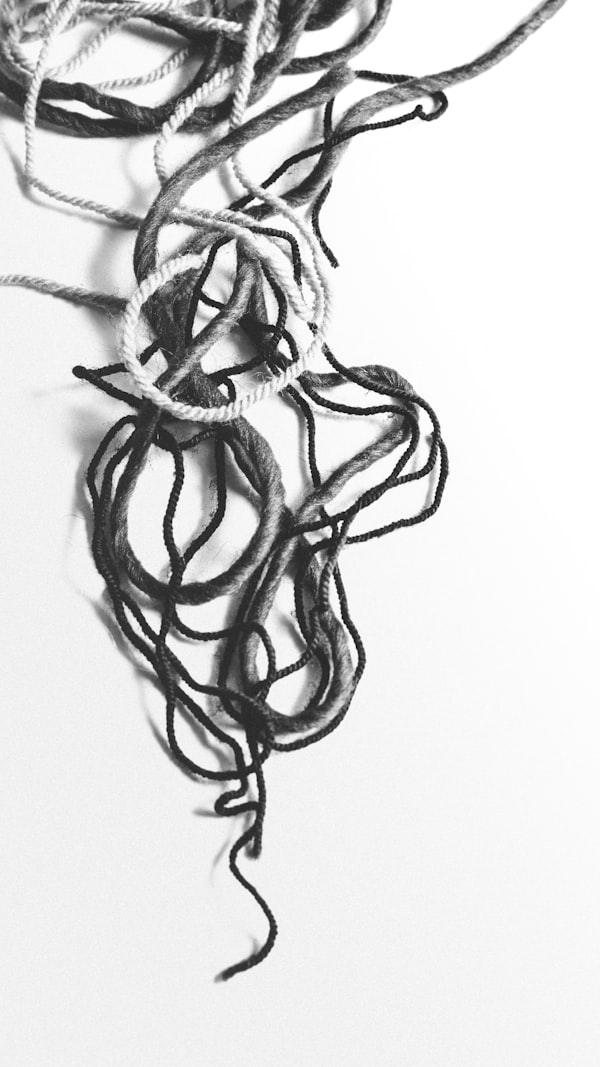

Due to Franz Kafka’s mysteriousness as a writer and purveyor of philosophical ideas, I can only guess at the full depths of what he’s getting at in this story. A writer compelling enough to draw a reader into a labyrinthine story or novel, Kafka also, in my experience, presents difficulties with a prose style that flows and eddies like water, leaving me bewildered at times, not knowing where the narrative thread has gone.

In this story, though, Kafka succeeds at creating a fictional situation based on a real “Hunger Artist” phenomenon, depicting onlookers expressing curiosity, repugnance, pity, contempt, and indifference, as in our world of televised cages.