Performance Review: Layna Wang's "bathtime?"

by Miri Verona

Layna Wang is an emerging artist and entrepreneur based in Chicago. A recent graduate of Lawrence University, Wang was the creative mind behind a recent performance art experience entitled “bathtime?”

The project was heavily informed by Wang’s lived experience, especially as a gender- and racially-ambiguous person who was abused during their education in the world of classical music. “It’s not one-off that I have experienced this pain in classical music and other systems which incentivize us to hate ourselves and each other, and it’s actually a privilege that I have a platform to address it and reclaim artistic agency,” Wang said.

I had the honor of participating in the labs as well as the performance of bathtime? over the past month. bathtime? took place at 7:30pm on Sunday, November 20th in Lawrence University’s Warch Campus Center just a day before finals week of Lawrence’s fall trimester.

In interrogating art and identity, Wang’s project asked large questions. These included “what is performance and a performing body?” as well as “who is encouraged to perform, in what ways, and why?” Wang’s collaborators explored these central themes in “laboratory” rehearsals with the “bathtime?” title, the physical centerpiece (an actual 250lb cast-iron bathtub Wang had acquired) and a three-hour room reservation looming in our minds as concrete anchors for what the project might turn out to be.

The community of musicians, studio artists, dancers and creatives which Wang coalesced around bathtime? invested an impressive amount of time and energy in the piece. It was no mystery to anyone involved that bathtime? (as its eponymous question mark reflects) contained planned and unplanned improvisations and uncertainties up until the last second of its performance. However, what bathtime? lacked in certainty it made up for in Wang’s impressive and infectious openness, sense of community, vulnerability, emphasis on consent and thoughtful creative vision in putting the experience together.

Wang’s sensibilities during the labs were inherently collaborative. While Wang would prompt various group improvisations that included explorations of movement, visual art and music, discussions which followed were open and empathetic dialogues for our feelings as collaborators: what we experienced, what we might change, how it fits into Wang’s project.

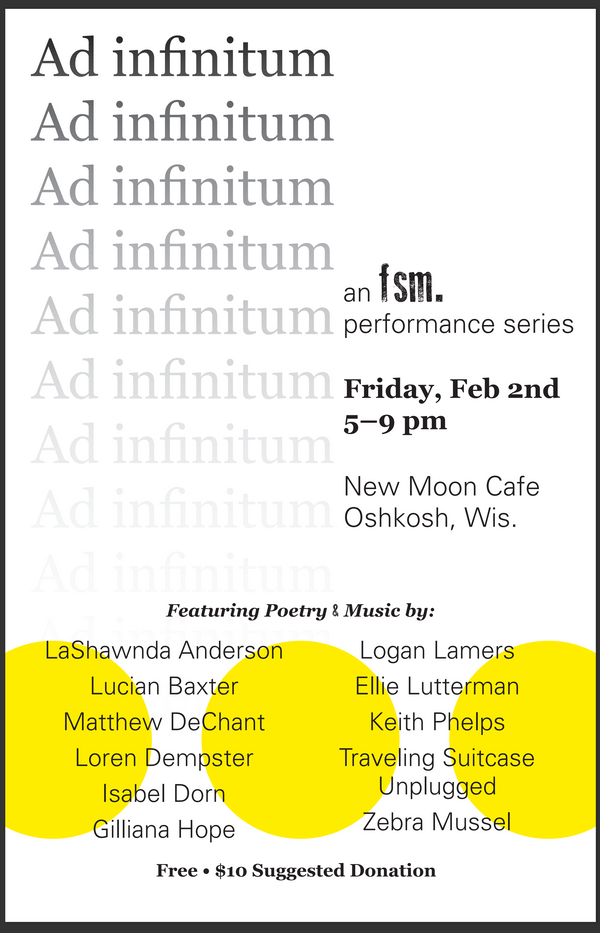

Initial ideas centered around a three-hour-long interactive artists’ salon which might include everything from collaborative drawing to a game of Jenga to a live email chain. The collaborators reveled in the open-ended creativity of Wang’s vision, but the rubbly pitfalls of incoherency loomed at least as strong. An important lesson came with the participation of Prof. Loren Dempster, one of Wang’s advisors, in one of the labs. He described how with the incredibly open-ended nature of Wang’s rehearsal, he couldn’t help feeling a disconnect while participating as an advisor to the project.

Wang echoed the disconnect as well given their and Dempster’s respective roles as student director and professor-advisor. “Prof. Dempster expressing his honest feelings made me realize how my intentions needed to shift,” Wang said. “As the director, I wanted to avoid perpetuating harmful power dynamics, but I needed to acknowledge these dynamics will always somehow be at play. Instead of wishing them away, I realized that they needed to be accounted for through a clearer structure.”

48 hours preceding the performance, Wang moved away from the open-ended format. Instead, working with the collaborators, Wang drew out a multi-scene script. “The script was a transcript of our improvised choices, informed by what we learned in our laboratories,” Wang said. “I was really happy when everyone’s input felt naturally a part of the process – it became less hierarchical when we felt safe around each other.”

The performance took just under an hour, centered around an intimately spotlit bathtub surrounded by large mirrors. Instrumentalists, dancers and performers filtered on and off center stage, performing various motives and improvisations. “Backstage” was unhidden on the sides of the audience seating not facing the bathtub; it included a lighting controller, props, collaborators moving about and a mic’d bucket of water and rag.

The nine-scene performance culminated with a deeply emotional scene featuring most of the collaborators and Wang intimately cuddled together on the floor humming in improvised harmony together. bathtime? was met with uproarious applause which led into an open space for discussion and more improvisation. “Having a fat, queer body and wearing a morph suit and then showing the audience exactly how I felt about wearing that morph suit and my feelings of being perceived by them was a hugely liberating experience... identity art is real,” Wang said in reflection.

Wang stated to the audience before the performance that the communal preparation of the project was the lion’s share of what made up the artistic experience of bathtime? For Wang, making an effort to share and expand the community of the project was always going to be a part of the project; fulfilling the capstone requirement, while a result, had very little to do with it. Despite sometimes frantic preparation and various uncertainties, through Wang’s open and empathy-driven approach they built an unforgettable, collaborative community of trust, of safety, of consent and of creative joy between us collaborators.