She Says? No, I Say!: Chinese Contemporary “feminist” Art

by Wenshu Wang

Chinese female artist Xiang Jing (b.1968) said in an interview, “I am not too sure that feminism is suitable or relevant to Chinese culture because China has never had a conscious awakening or any so-called female liberation movement initiated by Chinese women themselves.”1 The “feminism” she mentioned here refers to the Western ideology of Feminism that was rooted in the French Revolution (1789-1799). Xiang makes a significantimplication that the Western model of female liberation does not work in China. For Chinese women, it has rarely been possible for them to start and succeed in a female movement fighting for their rights.

How do contemporary artists encounter female issues in China? Is it possible to define feminist art in a Chinese context? With these questions in mind, I designed a virtual exhibition for the Global Modernisms class entitled “She Says? No, I Say.” This exhibition features ten artworks ranging from 1989 to 2017 created by contemporary Chinese female artists. I defined “Chinese feminist art” as artworks that address female artist’s self-consciousness of gender and actively speak up for women’s issues.

The title “She Says? No, I Say” indicates the necessity to hear from women themselves. Women are often “she/her.” When a woman appears as “I/me,” people are not used to it. Female’s behaviors are often restricted by others; female’s bodies are often depicted by others; female’s thoughts are often spoken by others. Thousands of years of traditional feudal culture in China has led to women’s objectification, submission, and marginalization. Aiming to assert women’s agency, this exhibition deals with women’s subjectivity.

Artists included in this exhibition are consciously aware of themselves being women. Their artworks convey various female issues related to either personal experience or broader thinking. Most importantly, they reflect Chinese female artists’ consideration of female’s individuality and desire to express themselves. Based on artists’ approaches and themes in their work, ten artworks are divided into three sections: “Reveal the Concealed,” “Articulate the Wounds,” and “Reinterpret the Body.”

I want to highlight some artworks from each section and give a brief illustration. Chen Lingyang (b.1975)’s From January to December, Twelve Month Flowers (1999-2000) is included in the section of “Reveal the Concealed.” This series of photographs depicts a female body with menstruation blood that is reflected through a traditional Chinese mirror accompanying a specific species of flowers. In traditional Chinese painting, the symbolic relationship between flower and mirror signifies beauty making the construct of femininity overt. Noteworthy, the representation of the naked body was never established in China’s pictorial history. Chen’s distortion of Chinese traditional femininity is a realization of women’s independence because the once unspeakable menstruation now is spoken. Overall, Chen’s work challenges Chinese taboos against nudity and a pervasive cultural disgust about menstrual blood.

The following section, “Articulate the Wounds” features three pieces of performance art. One of them was He Chengyao (b.1964)’s 99 Needles (2002). She asked a friend trained in Chinese medicine to pierce her entire body with acupuncture needles. He Chengyao

did this performance at the clinic where her friend worked during lunch hour. Due to the excessive number requested and limitation of time, He began to bleed from a spot above her right wrist. She became increasingly dizzy and eventually fainted. This performance piece is meant to underline her mother’s tragedy caused by China’s patriarchal society and brutal political campaign, and it also visualizes the wounds from a female’s perspective.He Chengyao was born out of wedlock, and her mother, unable to bear the societal scorn, became mentally ill when He was quite young. He’s grandmother tried multiple ways to cure her mother. Several people from a local military installation tried to treat He’s mother with acupuncture. Without medical training, they used the family’s wooden door as a table and held He’s mother down on it while they stuck her with needles in rough fashion. This kind of memory has never left He, hence she created this piece.

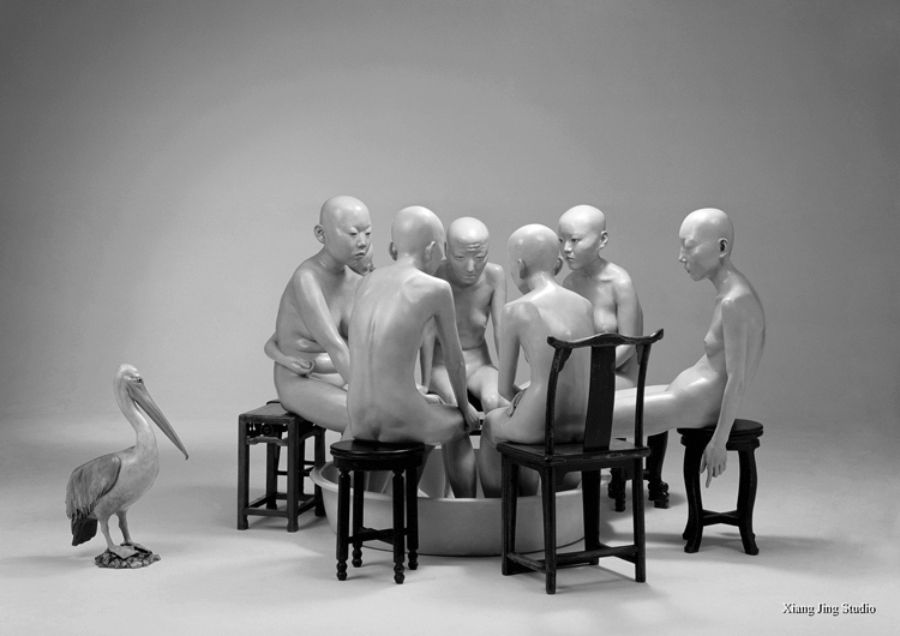

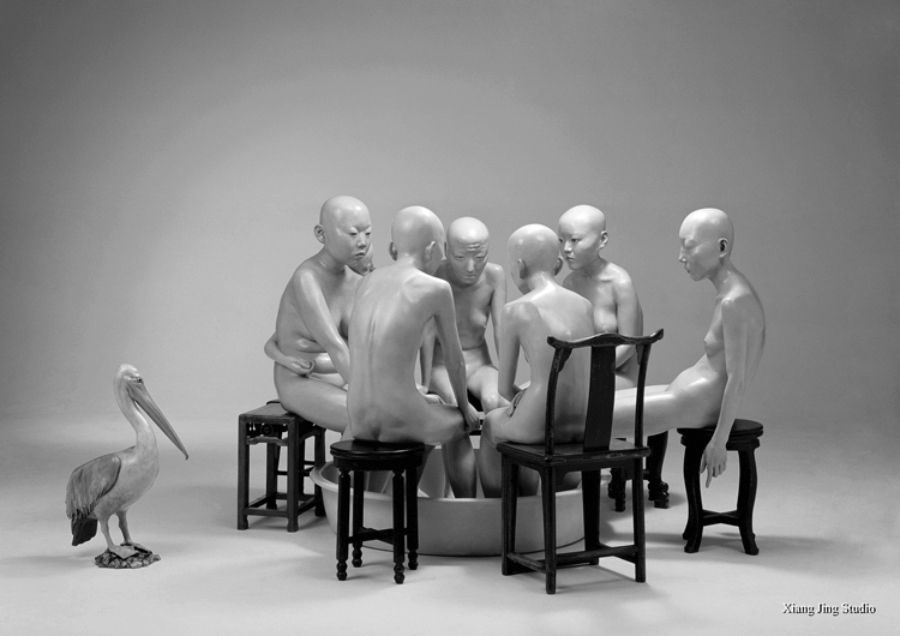

The final section, “Reinterpret the Body,” contains three artists who use the female body as a medium to incorporate different themes. Xiang Jing is a sculptor, and I saw her early work, Are a Hundred Playing You? Or Only One? (2007) in the Chazen Museum of Art. This artwork depicts a scene of foot bathing, where seven naked bald female figures sit on wooden chairs and a francolin stands next to the women. One of the women frowns and the other two lean close to each other. Her work does not come from reality, because it is unlikely in any culture that a group of people would get naked and bathe their feet together. It was intriguing to see how this work occupy the museum space because viewers need to walk around the sculpture to see the details. The imperfect female bodies sharply contrast to the ideal female bodies we usually see in media, and Xiang succeeds in creating an uncanny feeling for the viewers.

After I finished this project on Chinese feminist art, I was funded by the Arthur A. Thrall Student Travel Fund at Lawrence University to interview Xiang Jing at her studio in Beijing. Compared to feminist art, Xiang was inclined to describe her sculpture as individualistic art. Xiang indicates that her work is more about self and ego instead of social issues. Things change so rapidly and incomprehensibly in the external world, so Xiang focuses more on the internality or immanence of humans. Initially, I wanted to use this interview as a resource to complete my capstone paper, but it turns out that Xiang did not fully agree with my understanding of Chinese feminist art. Therefore, I wrote on another Chinese artist in my capstone paper. One of the challenging aspects for art historians to study contemporary art is the divergence between scholars and artists. Which group has a more authoritative voice? I wish to explore more on this controversial question as I move forward.

If you are interested in my virtual exhibition and want to see all the artworks, please visit

https://thor.lawrence.edu/omeka/arhi333/s/chinese-feminist- art/page/introduction for a full list of art images and wall labels.

Images referenced in the article:

1. Chen Lingyang (Chinese, b.1975), Twelve Month Flowers, 1999–2000, Chromogenic print, Dimensions various, Courtesy the artist and The Walther Collection.

2. He Chengyao (Chinese, b.1964), 99 Needles, 2002, Beijing, Performance photo, video.

3. Xiang Jing (Chinese, b. 1968), Are a Hundred Playing You? Or Only One?, 2007, Fiberglass, acrylic paint, wood.