Book Review: The Blunderer

by Vic Neptune

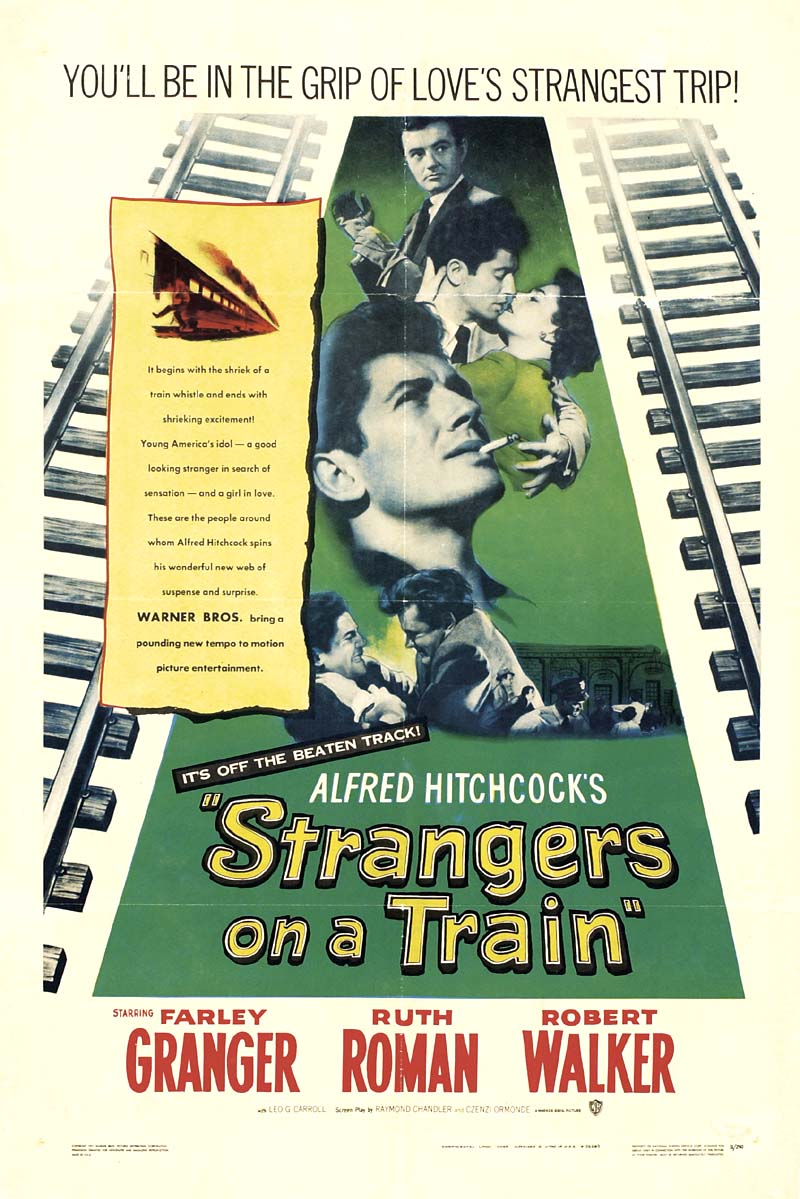

Patricia Highsmith wrote Strangers on a Train (1950), adapted for the screen by Alfred Hitchcock the following year. That novel and its film adaptation feature a pair of fatally linked protagonists, one of them a psychopath, the other a clean cut tennis pro whose upwardly mobile life is nearly ruined by the other’s mad scheme to exchange murders.

“I do your murder, you do mine.”

Guy, the tennis star, has a wife who’s become a serious burden on his life. He’s in love with another woman, too. Bruno, the other protagonist, hates his father. He takes seriously Guy’s mistake in not taking Bruno seriously enough. When Guy’s wife ends up strangled to death, Bruno proceeds to pester him about coming through with the other end of the homicidal bargain.

Strangers on a Train is a wild story delving into a dark territory of the mind, underlying ordinary life. Highsmith’s The Blunderer (1954) uses the same fatally linked two character premise, but with a different take on the “good” half of the featured duo. One protagonist, a Newark, New Jersey bookshop proprietor, Melchior Kimmel, is forty years old, overweight, badly near-sighted, an emigrant from Austria, and married to Helen, whom he kills in the first chapter. This act, described in brutal detail, happens at the climax of a long failing marriage characterized by adultery on her part, with resulting humiliation felt by Kimmel, since there’s nothing secret about it among the couple’s acquaintances and friends.

After a final argument, Helen Kimmel leaves him to stay with her sister, bussing from Newark to Albany, New York. Melchior Kimmel follows in his car. When the bus makes a scheduled fifteen minute stop at a roadside diner, Kimmel calls out to his wife as she’s getting out. Irritated, she nevertheless agrees to speak with him one more time. Leading her into the darkness behind some bushes, he beats and stabs her to death. Afterwards, no one suspects him--it appears to be a random killing.

In Chapter 2, the reader meets the other protagonist, Walter Stackhouse, a junior partner in a successful New York law firm, and his wife, Clara, a real estate agent. They live in a quiet neighborhood in a pleasant part of Long Island. They have a maid who works mornings and evenings, makes their breakfasts and dinners, cleans and straightens. Clara has a fox terrier named Jeff. Clara dotes on the dog, paying more attention to Jeff than to Walter, yet, on the surface, everything seems placid: 1950s American upper middle class A-Okay. The Stackhouses have numerous friends as well as colleagues in their respective professions. They regularly attend and give parties.

Clara picks at and criticizes most everything Walter does and says. By contrast, she lets Jeff the dog wander around unleashed in a restaurant.

The early chapters dealing with the Stackhouse marriage are the funny parts of the novel. Humor mixed with pathos. With pathos, one feels pity for someone or for a situation. Walter, the blunderer of the title, experiences growing frustration with Clara. She can’t be satisfied with anything he proposes, gets on his case over the most trivial matters, expresses a withering jealous attitude when he simply mentions the name of a woman at a party.

Walter, through a series of accidental actions that seem fated to occur, becomes fascinated with a newspaper account of Helen Kimmel’s murder. By a sheer lucky guess, he believes Mr. Kimmel killed his wife and that he followed the bus to Albany, murdering her during the scheduled stop. When Clara Stackhouse busses to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania to see her dying mother, Walter follows it, pulls over at a roadside diner where the bus makes a stop, and spends fifteen or twenty minutes trying to find Helen. The impulse to kill her passes during this desperate search. She got off the bus, but what happened to her? He asks a man in the diner about how long the bus will stick around. The man gets a good look at Walter’s face.

The next day, Walter gets a call informing him of the apparent suicide of his wife. Her body had been found at the bottom of a cliff near the roadside diner. Walter knows she probably killed herself because she’d taken pills to do just that a month beforehand.

Walter comes under suspicion because, on an impulse, before Clara’s death, he drove to Newark to meet Kimmel in the bookshop. This encounter causes Kimmel to be wary of Walter, as he should be, because Walter, sighted at the roadside diner the night Clara died, has attracted the attention of Lieutenant Lawrence Corby, an ambitious homicide detective who comes to investigate both Kimmel and Walter simultaneously.

Lieutenant Corby, himself an unsavory personality, smiling, sarcastic, concealing underneath his friendly surface a fierce violence unleashed numerous times on Kimmel to get him to confess, tries to play Kimmel and Walter against each other, but the pair both hate Corby so much they end up cooperating by not revealing until late in the game that Walter first met Kimmel in the bookshop and that Walter got his idea about following Clara’s bus from the newspaper account of Helen Kimmel’s murder.

The story leads to a late night fatal meeting between Kimmel and Walter in Central Park. Corby, for all his coercions, has been unable to get Walter to confess.

Of Highsmith’s work, I’ve only read this novel and Strangers on a Train, the latter an excellent tale rivaling in quality Hitchcock’s film adaptation. Still, Strangers, compared to The Blunderer, is a relatively simple story, the two protagonists, Bruno and Guy, more black and white than Kimmel and Walter. Guy is a straight-laced all-American athlete type whereas Bruno is a dark-minded though charming nutcase. Walter, by contrast, though a nice guy, is nevertheless someone highly pressured by his bad marriage. Though competent as a lawyer, he’s a much put upon oaf.

Kimmel’s lurking violence mirrors Corby’s. Though the reader first encounters Kimmel going about killing his wife, his later horrible encounters with an out of control sadistic cop cause a sense of powerful revulsion towards this “tool of justice” Lieutenant Corby. After I read the final page, I assumed that once Kimmel gives his confession, Corby will probably get promoted for solving the Kimmel case, an ending hanging over the shocking conclusion (which I won’t reveal) like a fermata in a symphony, a pause of silence.

I read this novel in three days--it stunned me. As far as I can tell from Strangers on a Train and The Blunderer, Patricia Highsmith was one of the great psychological fiction writers. Horrifying and funny, The Blunderer, in trade paperback, is one of many Highsmith novels available at the Oshkosh Public Library. I plan to read more of her stuff.

Vic Neptune writes, makes movies (YouTube Channel John Berner), collages, paintings. Movies made as Rhombus. Film criticism based on thousands of movies of all eras seen. Strong interest in literature: Shakespeare, Thomas Mann, Jack London, Robert E. Howard, Joan Didion, Philip K. Dick, and many others. History and religion other interests also. Favorite filmmakers: Jean-Luc Godard, Michelangelo Antonioni, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and Federico Fellini. Life without art is art without life.