Exhibition Review: CommonPlace*: David Graham & Terri Warpinski

*The Commonly Found or Seen; Ordinary, Unremarkable

by Carol Emmons

CommonPlace is an especially apt title for this dual exhibition by David Graham and Terri Warpinski. They have both relocated from significant careers elsewhere, and are now partners in both life and newARTSpace, their studio/gallery in De Pere. In addition, they are both using photographic means to explore Wisconsin.

At first glance, there might not seem to be much common ground here: Graham works in color, and Warpinski in black and white. Graham’s pieces are framed, standard-sized (up to 24 x 35”) mostly horizontal “straight” photographic works. Warpinski utilizes alternative presentations (accordion books, installations) with often vertical, large-scale, non-traditional materials (e.g., washi papers and silk). However, their common ground becomes more apparent with a closer look.

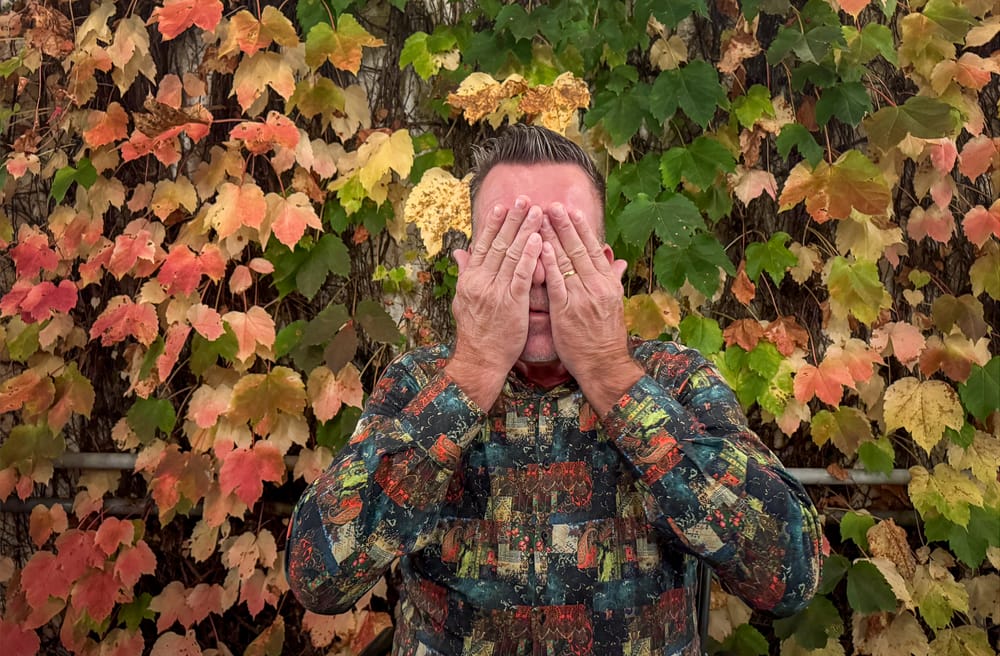

In David Graham’s works, one is struck by the strong formal relationships—especially pure or saturated colors that repeat within a composition, supplying underlying structure. For example, in Green Bay, WI (Angelina’s) 2024, a central male figure is nearly completely camouflaged by the similarity between his shirt, flesh tones, and the surrounding foliage. It is rare for Graham to focus on people in these works, but that is mitigated here by the subject’s hands covering his face.

Angelina’s is also a bit of an anomaly in that Graham more often features long shots than close-ups, presenting his subjects in contextual environments. A frontal, symmetrical composition is not uncommon for Graham, but he regularly employs perspectival angles, which suggest deeper space, usually facilitated by considerable depth of field (sharp focus). In addition, the scenes tend to be fairly complex, distinguishing them from what’s become the iconic Wes Anderson approach.

Among his works, some present primarily as essays on color, shape, repetition and textural variety such as the oxymoronic pink greenhouse of Suamico, WI 2023. Others feature images within images (Munising, MI 2023 or Baileys Harbor, WI 2021) where figure and ground, reality and illusion are comingled. The result encompasses both sly wit and questions about the nature of representation and our susceptibility to such illusion.

At times Graham savors the casual accident, such as a man in green shirt and red pants in front of his colorful Mondrian-esque garage door in DePere, WI 2021. Other images celebrate the results of a particular point of view: in Allouez, WI (Dino) 2023 a woman’s head on a billboard and that of a green dinosaur are juxtaposed through a very particular angle of view, and further linked by the matching green stripes of the gas station portico. This meticulous care in his shot-making is consistent throughout his body of work.

Whether examining the everyday or the surreal, there is a sense of humor throughout all these works. This is partly buoyed by the bright colors and often unusual subjects. Yet there is no condescension in Graham’s approach: he documents the delights and absurdities of the human environment with affection.

Terri Warpinski is also at work documenting the environment, but focuses on woodland scenes and what we call “nature,” though she is especially interested in investigating those areas which have been altered through human intervention and which she sees as urgently in need of restoration.

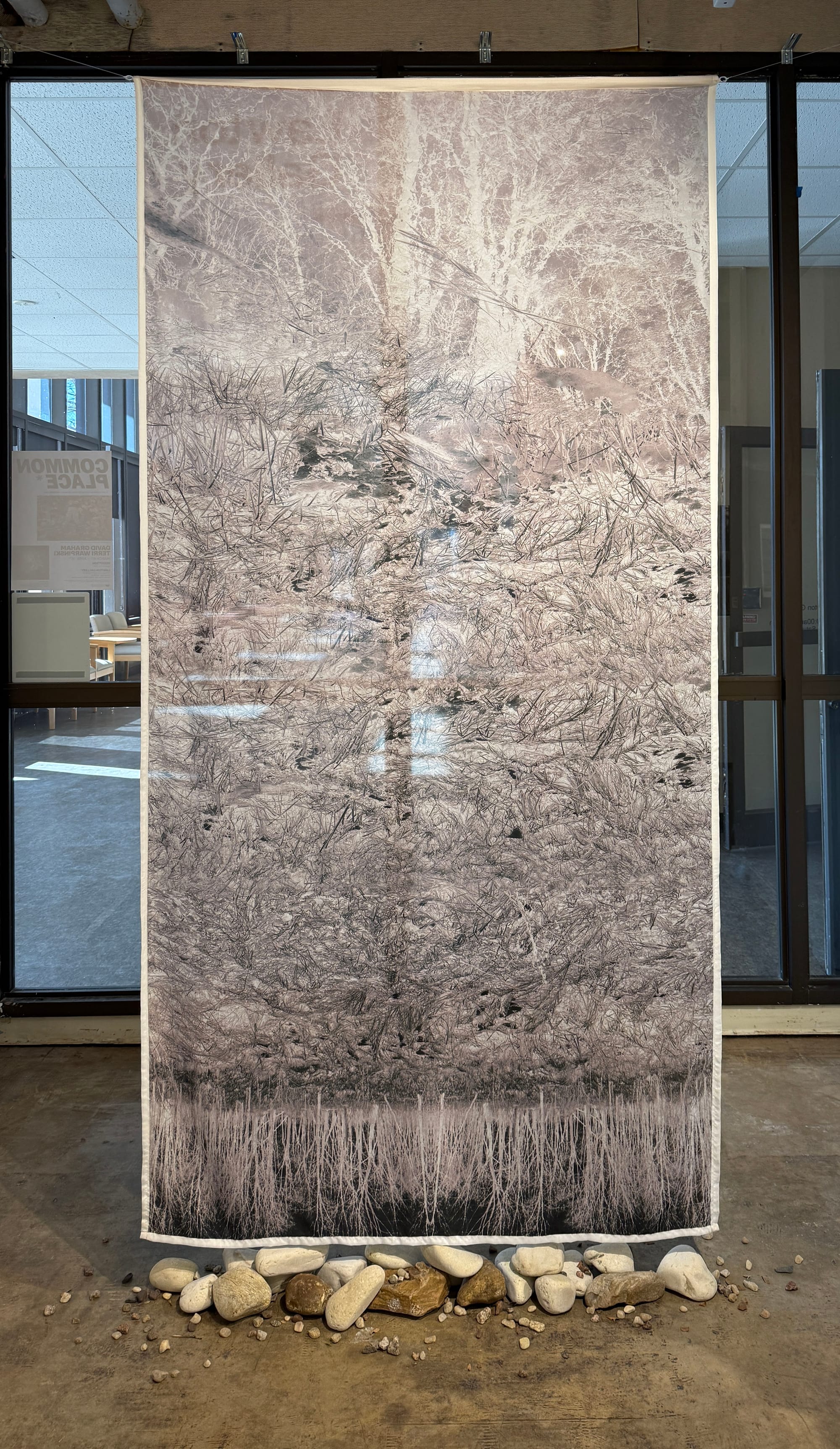

These images are not classically beautiful, calendar-art landscapes. They are intricate compositions that often confuse the eye. Some entail manipulation of scenes and their reflection, some are presented as negatives, and all feature elaborate patterns. That is, they admit of unruliness and complexity–much like the areas they represent. In this regard, Warpinski’s Restless Earth and Constant Movement titles are particularly pertinent.

Some of the scrolls have white edges, echoing the old film tradition of verification borders (indicating an image was printed without cropping). Beyond technical considerations, these borders emphasize and enhance the whites in the images, an important element given the density of greys and blacks in the subjects. The results are elaborate visual textures, with values ranging from bleached out white to black with a multitude of intermediate greys.

One way in which the restlessness is tamed is through lines of continuation. This is especially evident in Mapping the Understory (2024) where the artist’s book is presented as a gridded but continuous scene, branches connecting from one cell to another. This technique is employed more subtly in the Constant Movement Suite (2024) where some tree branches from the lower scenes (medium to long shots) link to lines within the nest close-ups immediately above. This construction works less well when physically literal in Restless Earth: Ground Water [Kangaroo Lake](2024), where actual birch logs are aligned with the image.

The scroll presentation is especially compelling in Restless Earth: Ephemeros [Sensiba] (2023), which occupies the gallery’s window, making full use of air movements and natural light. This placement suggests the notion of a photograph as a window into the world, but the work’s pronounced evanescence counters mistaking it for reality. The printing of the image as a negative (tree trunks are white, sky becomes dark) suggests a scene of hoarfrost, with everything etched in white. These inversions and reflections carry metaphorical weight, too—perhaps suggesting our skewed perceptions of the environment or the trees as vanishing ghosts.

Arranged below Ephemeros is a line of small rocks and stones, creating a tangible grounding for the image. They relate nicely to the concrete floor and visually anchor the ephemeral silk. This recalls Samuel Johnson’s rejoinder to Bishop Berkeley’s argument that reality was created strictly by minds, not composed of matter. Johnson countered that notion by kicking a rock and saying, “I refute it thus.” In a similar way, Warpinski’s use of found rocks, birds’ nests, and logs reiterates the tangible reality of the world.

The curator John Szarkowski proposed a dualism of photographs as either windows (documentations of the world) or mirrors (reflecting the photographer’s sensibility). Warpinski scrambles this opposition, incorporating both. And while it might seem that Graham is operating strictly within the “window,” the mindfulness and consistency of his choices builds a very specific Graham universe of Americana.

The common ground connecting Graham and Warpinski is not merely impeccable craftsmanship and strong formal concerns, or the construction of a world view, but investigations of common places that tell a story of who we are. The titles of some of Graham’s books on display in the gallery emphasize this: American Beauty (1987), Only in America: Some Unexpected Scenery (1991), and In Plain Sight (2022).

In his statement, Graham notes that he “… explores how Americans express themselves through their environments…. The result is a series of photographs which delve into the complex weave of image, symbol and reality that we see as America at its finest.” Similarly, Warpinski explains that she “... explores the complex relationship between personal, cultural and natural histories ...” and seeks to construct a narrative addressing “... the accumulation of knowledge and the shadow of memory embedded in place.”

The word “commonplace” not only means “ordinary,” but refers to books created by individuals as repositories of sayings and other information. Commonplace books trace back to antiquity, but were especially popular in the Renaissance and nineteenth century. We might see David Graham and Terri Warpinski as proposing our environment—both human and natural—as such a commonplace, tracking our attitudes and values, aesthetics and ideals. We only need to pay attention, and it is inscribed before us.

CommonPlace: David Graham & Terri Warpinski

March 6 – April 18, 2025

Closing Reception April 17th, 2025, 4–7pm

Lawton Gallery, University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, Theater Hall 2nd floor; Monday-Saturday 10-3

Carol Emmons is an installation artist and Professor Emerita of Art at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay.