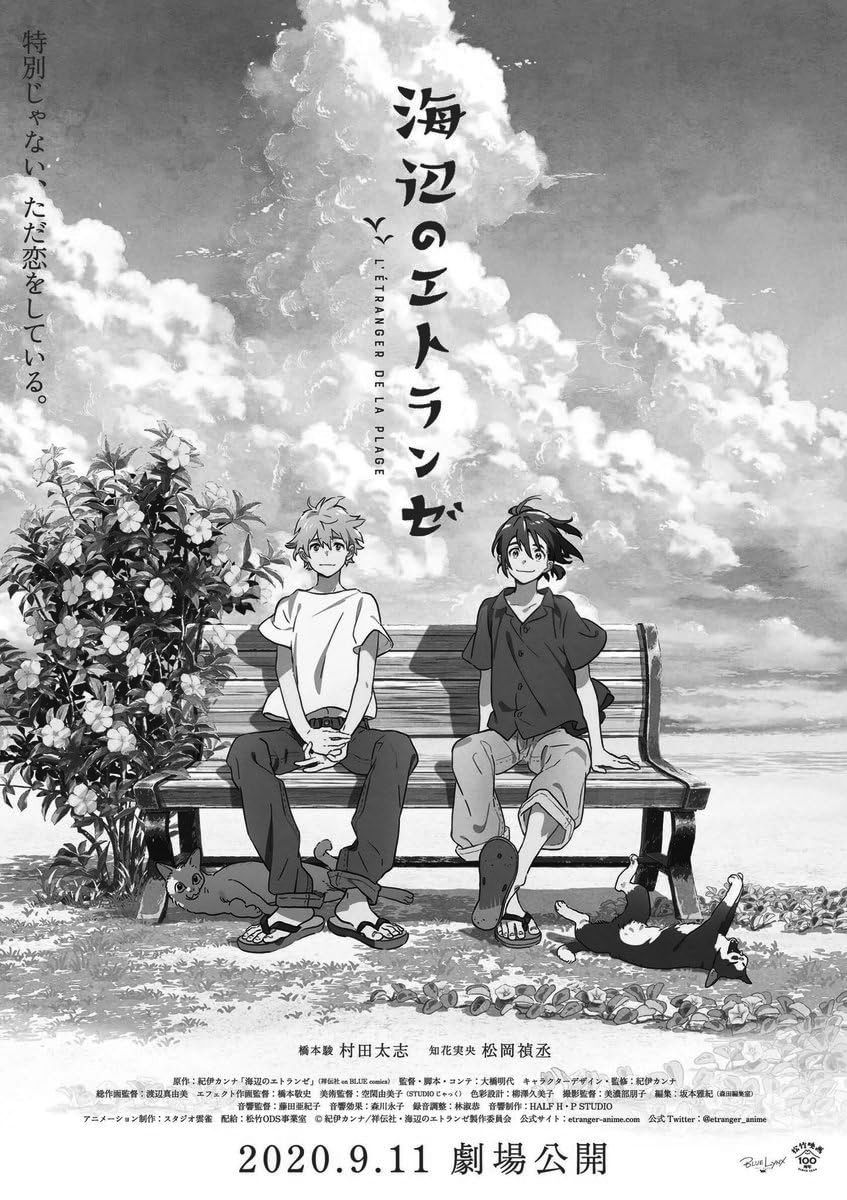

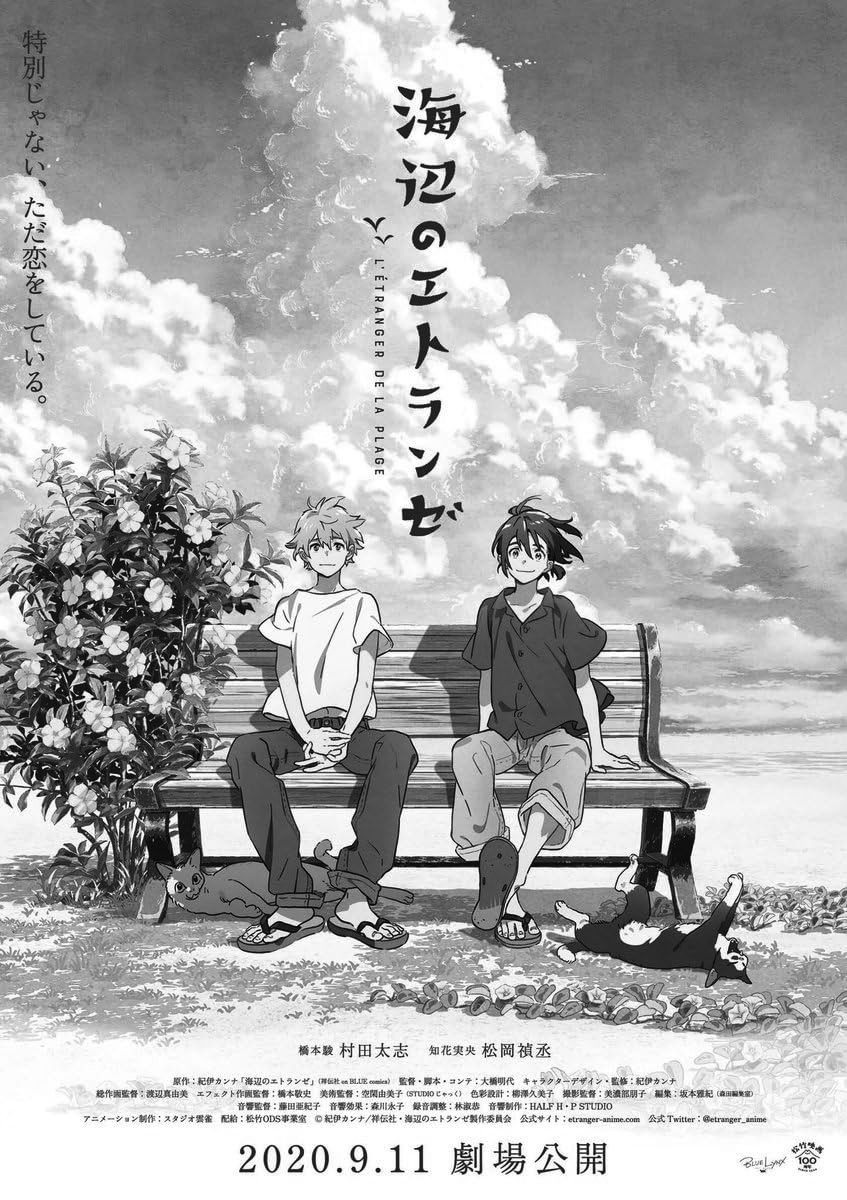

Film Review: The Romantic Revolution of The Stranger by the Shore

by Blair E. Vandehey

On an island far from the home he ran from, Shun Hashimoto (Jessie James Grelle), an author struggling to accept his homosexual identity, meets recently orphaned Mio Chibana (Justin Briner). However, their budding romance is overshadowed by Mio’s transfer to an orphanage on the Japanese mainland. Three years later, Mio returns with Shun in mind and heart – only to find the author pushing him away. Furthermore, Shun’s ex-fiance Sakurako (Amber Lee Connors) arrives on the island with a demand he return home to be with his dying father – the same man who drove him away. In fifty heartfelt – and at times, heartbreaking – minutes, Akiyo Ôhashi’s The Stranger by the Shore (2020) adapted from Kii Kanna’s L’étranger de la Plage redefines the narrative of a love story as the two young men learn to love both themselves and each other in spite of external and internal challenges.

Rather than the characters reacting as the plot develops, Ôhashi daringly flips the classic formula of romantic storytelling; the plot of Stranger by the Shore reacts as the characters develop. One of the driving tensions in the film is whether the flickering romance between Shun and Mio will be extinguished or ignited. Instead of being determined by a plot element, the resolution is determined by how well Shun can grow to accept a love he deems unacceptable as he interacts with the world of the film. In tandem, the plot following Shun’s decision whether or not to leave Mio and visit his father does not progress until Mio discovers his own independence and the strength to tell the man he loves to go (even if it pains him to do so). To stake The Stranger by the Shore’s happy ending on character development subverts the viewer’s expectation that romance is the ultimatum and instead innovatively highlights how each character grows in pursuit of love.

Dichotomy is the most heartbreaking strategy deployed by Ôhashi. Shun’s struggle to come to terms with his sexuality is fogged by his experiences with homophobic friends and family. Shun accepts that he loves Mio, but at the same time, he cannot fathom the risk that his love may subject Mio to that same trauma. Thus, a painful dichotomy of yearning to offer his heart to Mio while pushing him away in hopes of sparing him hardships is created. The Stranger by the Shore assumes a third person limited point of view, but allows the viewer to experience the story through the deuteragonist Mio’s eyes in addition to Shun’s. Mio’s dichotomic struggle emerges from having waited three long years to pursue his love for Shun, but recognizing the importance of family – having had two parents pass away – and wishing for his lover to cherish what he has before it’s too late.

Despite the prevalence of conflict, Ôhashi takes a bold step in refusing to vilify any of the characters. Instead, she demands an impartial empathy from her audience. Perhaps the most compelling example is that of Sakurako, who, despite being in love with Shun in tandem with Mio, is never framed as an antagonist. In the genre of romance, filmmakers often fling derogatory titles such as ‘homewrecker’ onto the romantic rival and label them the ‘bad guy.’ However, Ôhashi not only refuses to write Sakurako as the villain but amplifies the tragic situation surrounding her unrequited love. It’s not Shun’s fault he cannot love her, nor is she to blame for her feelings. Sakurako is simply a victim of circumstance, a refreshing outlook on the heavily villainized romantic rival trope.

Evolving the romantic narrative on every level of storytelling is what makes The Stranger by the Shore a trailblazer in film. One small–yet powerful–choice Ôhashi adds is communication between Shun and Mio in their first night together. Throughout the entire scene, the two are constantly checking in with one another, especially to acquire consent to further action. Unlike anything I have ever seen before onscreen, consent in The Stranger by the Shore is never a closed process; instead, it is recognized as ongoing and, most importantly, subject to change. At one point after the initial assent, Mio perceives that Shun may be overwhelmed–that his desire to engage may be different from when they began–and draws back for a moment to gain affirmation either way. Only when Shun offers assurance and pulls Mio close do the two continue. While communication seems like a simple aspect of an intimate moment, its rarity in contemporary film makes Stranger by the Shore stand out against the typical romance.

To rework the idea of what a love story can achieve is a feat in itself. Yet, Ôhashi’s romantic coming-of-age film completely sheds the genre’s expectations. Left over from the dismantlement was room for The Stranger by the Shore to be rebirthed into the beautifully innovative story it is.

Blair E. Vandehey is an Appleton-based writer, daydreamer, and lover of all things pop culture. She is currently working towards a degree in Creative Writing at Lawrence University.