Book Review: The Titular Truth of wild is she

by Blair E. Vandehey

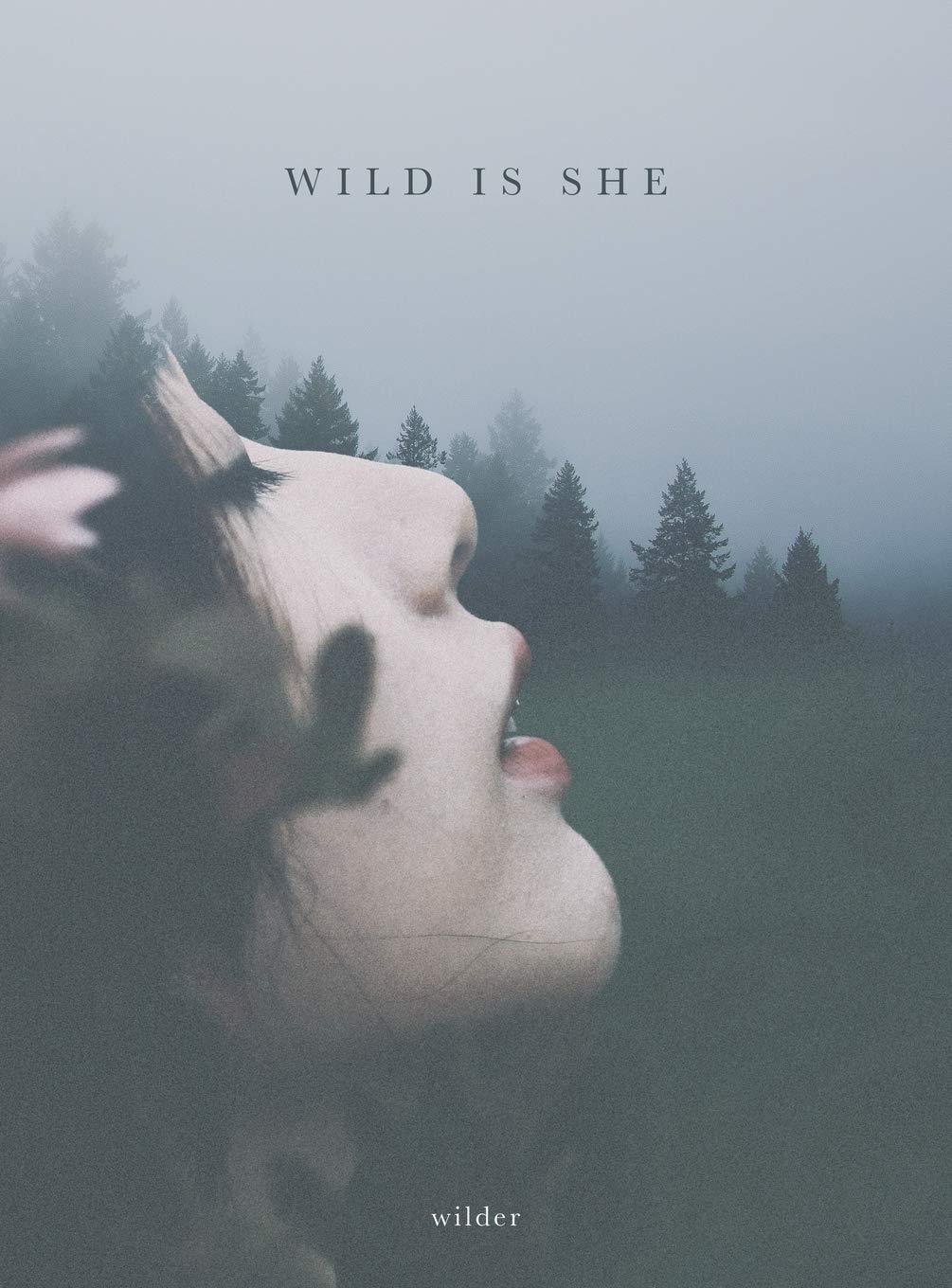

Lines exist as parameters. The genre of contemporary poetry knows lines better than many other literary mediums; poetry within the overused boundaries of love, loss, and healing dominate bookshelves. While there is nothing inherently wrong with this ‘big three’—some of the best pieces I have ever read explore these subjects—lines also exist to be crossed and blurred. Wilder’s debut work wild is she does just that—it strays from the lines of cliché with abandon.

There is an infatuation with the idea of finding oneself or being found in contemporary poetry. While each poet has a unique experience in their journey back to themself, the overall concept is heavily downtrodden. Wilder, too, explores these ideas, but she strays from the formulaic path that many other poets take; rather than treating ‘lost’ as something to escape from, our author allows herself time to roam, embracing the moments only a soul adrift can experience. While she acknowledges her wish to one day rediscover herself, she refuses to rush, instead choosing to welcome every adventure within her uncharted soul with open arms—we can only find ourselves because we get lost in the first place, after all. Thus, a gray area between the two is created. No longer is ‘lost’ used as a negative word as it is in innumerable other contemporary collections; instead, it is something wild is she teaches its readers to revere.

As the title suggests, wild is she is a tribute to the natural world. Throughout the collection, Wilder cries with the rain, exchanges pillow talk with the moon, and embraces the ocean, all of which have been given their own distinct characters and arcs. Our author has always been an expert at blurring lines, and her characterization of otherwise nonliving entities is no exception; not only does she tap into the space between poetry and narrative, but the empathetic way she writes marries the ideas of simple personification and imperfect, nuanced humanization. Even in their faults, their humanity is bolstered rather than diminished; the ocean may come off as somewhat cold, but is emotional disconnectedness not an exclusively human state of being?

Unlike the black-and-white nature of many contemporary poetry collections, Wilder’s love for nature does not constitute hatred for mankind. From cover to cover, she actively refuses to take a nihilistic stance on humanity—we, too, are part of the natural world, whether we realize it or not. The final poem in the section “Sparrow” is an excellent summary of what Wilder believes of being human; it alone is what makes us beautiful, and it alone is proof of our worth.

Wilder’s adoration for the human experience is most evident in the third section, “The Head & The Heart,” which recounts the stories of three different couples. It is divided into three parts: “Tarot & Winter,” “Harper & Bleü,” and “Rowan & Asher.” The first of the three is a fond recollection of a first love long lost to time. Through the persona of the inexperienced Winter, Wilder writes about the honeymoon phase of the young women, her musings complete with grand declarations of love for Tarot. As the parts go on, maturity develops; writing from Harper’s point of view, our author creates an intimate atmosphere through musings on familiar legs tangled in familiar sheets. Still, not every love can last forever, and Asher’s longing for the long-gone Rowan is a painful reminder of such. Assuming the former’s role, Wilder narrates his dichotomic struggle of wishing to hold on to the other despite the heartache it brings.

wild is she was written with a desire for connection: connection with oneself, connection with nature, connection between author and reader. The final section titled “Conversations in the Sky” (after all, what knows connection better than the shapes drawn between stars?) is dedicated to author-author connection; it is a home for works that Wilder co-authored with poets she considers dear to her. Many of the poems were written together by both authors, but the final piece of the section titled “SPACE” is written differently; it is a melancholic piece about a not-so-unrequited connection. Wilder writes alone on one page from the point of view of a girl who adored the night sky as a child and now yearns to know that it loves her too. Although it has no human voice to connect with the girl, nightfall, the persona of poet Zack Grey, reveals it has heard her all this time and vows to be an eternal home for her to return to. Even beyond the wistful words, the choice to collaborate is Wilder’s loudest cry for connection in wild is she.

“Who Is She?” The answer that follows prologues the collection, but also reflects Wilder’s poetic freedom: “she is wild and wild is she.”

Blair E. Vandehey is an Appleton-based writer, daydreamer, and lover of all things pop culture. She is currently working towards a degree in Creative Writing at Lawrence University.